Dear Mr. Potato Head

- The World Digested

- Aug 5, 2017

- 5 min read

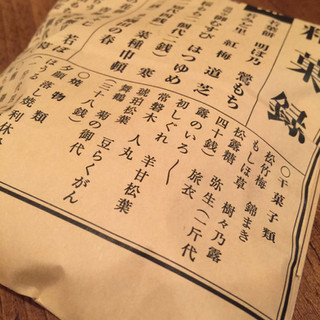

In the heart of quaint Ningyo-cho, one of the few districts in Tokyo which still wears Edo on its sleeve, or a shield against modernity, is “Kotobuki-Do” – a Japanese confectionary shop. The name Kotobuki-Do means an “Auspicious House,” and it must have conferred its auspice quite adequately as the shop had survived two World Wars since its establishment in 1884. While Kotobuki-Do makes other typical items involving the ubiquitous and universal red bean paste, their top-seller has always been the “Ougon Imo” – the Golden Potato.

Walking from the bright and busy street of Ningyocho into the dark and shadowy Kotobuki-Do is walking from the present back in time – from the current Heisei Period back into the Showa and Taisho, with a scent of the Meiji drifting in the dusty air. Dusty, yet fragrant – no, it is not the dust after all, but the “nikki” – Japanese cinnamon, more pungent and bitter than the common Sri Lankan or Indian cinnamon, like an incense.

The nose inhales the spicy air, while the eyes adjust themselves to the narrow interior. A glass counter stands guard right inside the sliding door, leaving barely enough room for a couple of customers to stand still. The other side of the counter is stacked with cases of, not golden eggs, but the Golden Potatoes.

“Please,” a glass of cold roasted tea magically slides over. Following the voice, eyes lower a foot in height, catching the profile of an old head-scarfed woman disappearing behind the counter.

The signature “Ougon Imo” is individually wrapped in a yellow tissue paper, which holds a dusty and crinkly brown tuber, the size of a fat finger. The wrinkly skin, once broken, reveals the namesake golden interior, looking uncannily like an ingenuously engineered miniature sweet potato; the only thing missing would have been the rising steam.

Japan has several kinds of potatoes and yams: the round “jagaimo” (the white potato of Mr. Potato Head), the sticky “yamaimo,” the hairy “satoimo” and the “satsumaimo” – the last is the sweet potato. The elongated purplish tubers, known also as yams, arrived in the southern state of Satsuma – the present-day Kagoshima – via China in the 16the century. Although it was cultivated in Satsuma, it remained unknown to the Main Island and thus to the people of Edo (now Tokyo), until Mr. Konyo Aoki, fondly remembered as Mr. Sweet Potato in Japan,* was appointed by the Edo Bakufu to study the crop as a way to fight the famine in the next century. Hence, the sweet potatoes became known as the “Satsuma-Imo” – the potatoes from Satsuma – in Japanese. (*In the Meguro Fudo Temple where he is buried, a festival of sweet potato is held each year on October 28, the anniversary of his death.)

Cheap, prolific and low-maintenance – these transplanted tubers were mixed into rice when the times were bad; and when it had become worst to worst, they replaced the revered white rice all together. Yet, almost as soon as these nutritious and noble vegetables arrived in the capital, the word “imo” came to be used as word of ridicule, signifying country bumpkins; and the samurai warriors from the State of Satsuma were laughed at for being “imo-zamurai” (potato samurai) and “imo-kusai” (smelling of potatoes) by the city folks.

Its uncouth image notwithstanding, satsumaimo became very popular in the Edo period. Even today, many cannot remain indifferent to the irresistible aroma of the charred stone-roasted sweet potatoes, especially in the winter, as these unassuming sweet potatoes are starchy and sweet, which only require a simple slow-roasting to draw out the caramel flavor.

At the same time, its wide availability spurred creativity, meriting its own edition in the popular Edo cookbook series (“Hyakuchin”) of one hundred recipes (the most popular, however, was the Tofu 100), and it was one of the first ingredient to be incorporated into the Western/European style of cooking when Japan finally opened its borders. A “Sweet Potato” was invented during the Meiji Period; it is made of mashed sweet potato, butter, cream and egg, and often spiced with cinnamon or nutmeg – not dissimilar to a sweet potato pie – but instead of a crust, it is often baked in its own skin.

The “Ougon Imo” of Kotobuki-Do was also created at the end of the tumultuous time of Meiji. Redolent of the piquant Japanese cinnamon on the one hand, moist and mellow on the other, the fluffy creation is just big enough to finish with a cup of tea, savoring and marveling that the “Ougon Imo” not only looked like a roasted sweet “satsumaimo” but also tasted like it. In fact, the flavor resembles the aforesaid “Sweet Potato” but without the addition of cream and butter – almost like re-Japanizing, the Japanized Western-style dessert.

Marvelous, because despite its name, the “Golden Potato” contains no potato, no yam and definitely no sweet potato – Satsuma or otherwise. Instead, the yellow stuffing of the “Ougon Imo” is a traditional “kimi-an” – made of white bean paste and egg yolk. Shaped then skewered, the paste is grilled at a high heat like a kebab. Once it is cooled, it is given a generous coat of the Japanese cinnamon. Theoretically, the high heat causes the air to balloon, thus creating the facsimile soft skin, while it in turn keeps the starchy interior fluffy and moist. But that is neither here nor there.

In the gloom of the shop, the mind reflects on the good old days when human ambitions only aspired to imitate potatoes; and human pretension only extended so far to such humble and simple vegetables. It is certainly a joke as one “Ougon Imo” costs as much as a bag of the real sweet potatoes, but played with a twinkle which lights the heart.

“Ougon Imo” is not alone in the art of imitation, however. There are the “Satsuma-Yaki” in Osaka and Nara, and the “Wakasa-Imo” in Hokkaido. While all strive to be sweet potatoes with varying degrees of verisimilitude, each interprets and invents the method of imitation in its own ingenuous way. For example, the “Satsuma-yaki” of Osaka is made of refined red bean paste, instead of white, and has a thicker and harder shell. As a matter of fact, although not sweet potato, there is also the “pomme de terre” in France, which is made of crumbled old madeleines and dusted with cocoa powder, which derives its name from the white potato, (the name “pomme de terre” is the French word for white potato (although the literal translation will be “apple of the earth”).

Is there such a thing as universal memory? Shared by all humanity across the world?

As the humanity strides forward forcefully in to faster and fancier times, these innocent mockeries are little warnings to us not to forget our ability to laugh at ourselves. In addition, these rustic mimicries seem to convey our deeper desire in wishing to return to the native and the primitive, and perhaps even the primordial. After all, monkeys are known to wash their sweet potatoes in the ocean, for a bit of the salty and the sweet.

What do you think, Mr. Potato Head?

Kotobuki-Do (壽堂)

TEL: 03-3666-4804

Address: 2-1-4 Nihonbashi Ningyocho, Chuo-ku, Tokyo.

Comments